Aircraft engine blades are in a complex and harsh working environment for a long time, and are prone to various types of damage defects. It is expensive to replace blades, and research on blade repair and remanufacturing technology has huge economic benefits. Aircraft engine blades are mainly divided into two categories: turbine blades and fan/compressor blades. Turbine blades usually use nickel-based high-temperature alloys, while fan/compressor blades mainly use titanium alloys, and some use nickel-based high-temperature alloys. The differences in materials and working environments of turbine blades and fan/compressor blades result in different common types of damage, resulting in different repair methods and performance indicators that need to be achieved after repair. This paper analyzes and discusses the repair methods and key technologies currently used for the two types of common damage defects in aircraft engine blades, aiming to provide a theoretical basis for achieving high-quality repair and remanufacturing of aircraft engine blades.

In aircraft engines, turbine and fan/compressor rotor blades are subject to long-term harsh environments such as centrifugal loads, thermal stress, and corrosion, and have extremely high performance requirements. They are listed as one of the most core components in aircraft engine manufacturing, and their manufacturing accounts for more than 30% of the workload of the entire engine manufacturing [1–3]. Being in a harsh and complex working environment for a long time, rotor blades are prone to defects such as cracks, blade tip wear, and fracture damage. The cost of repairing blades is only 20% of the cost of manufacturing the entire blade. Therefore, research on aircraft engine blade repair technology is conducive to extending the service life of blades, reducing manufacturing costs, and has huge economic benefits.

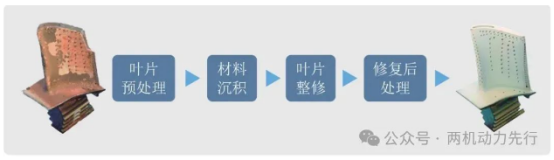

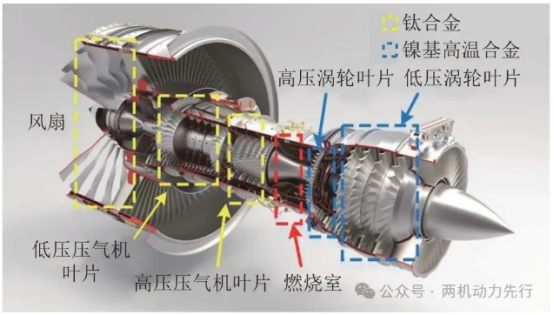

The repair and remanufacturing of aircraft engine blades mainly includes the following four steps [4]:blade pretreatment (including blade cleaning [5], three-dimensional inspection and geometric reconstruction [6–7], etc.); material deposition (including the use of advanced welding and connection technology to complete the filling and accumulation of missing materials [8–10], performance recovery heat treatment [11–13], etc.); blade refurbishment (including machining methods such as grinding and polishing [14]); post-repair treatment (including surface coating [15–16] and strengthening treatment [17], etc.), as shown in Figure 1. Among them, material deposition is the key to ensuring the mechanical properties of the blade after repair. The main components and materials of aircraft engine blades are shown in Figure 2. For different materials and different defect forms, the corresponding repair method research is the basis for achieving high-quality repair and remanufacturing of damaged blades. This paper takes nickel-based high-temperature alloy turbine blades and titanium alloy fan/compressor blades as the objects, discusses and analyzes the repair methods and key technologies used for different aircraft engine blade damage types at this stage, and explains their advantages and disadvantages.

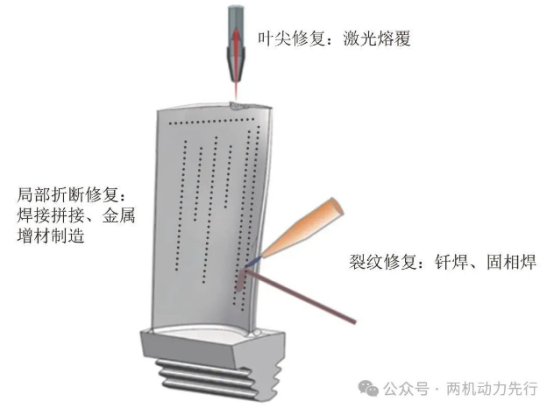

Nickel-based high-temperature alloy turbine blades work in an environment of high-temperature combustion gas and complex stress for a long time, and the blades often have defects such as fatigue thermal cracks, small-area surface damage (blade tip wear and corrosion damage), and fatigue fractures. Since the safety of turbine blade fatigue fracture repair is relatively low, they are generally replaced directly after fatigue fracture occurs without welding repair. The two common types of defects and repair methods of turbine blades are shown in Figure 3 [4]. The following will introduce the repair methods of these two types of defects of nickel-based high-temperature alloy turbine blades respectively.

Brazing and solid phase welding repair methods are generally used to repair turbine blade crack defects, mainly including: vacuum brazing, transient liquid phase diffusion bonding, activated diffusion welding and powder metallurgy remanufacturing repair methods.

Shan et al. [18] used the beam vacuum brazing method to repair cracks in ChS88 nickel-based alloy blades using Ni-Cr-B-Si and Ni-Cr-Zr brazing fillers. The results showed that compared with Ni-Cr-B-Si brazing filler metal, the Zr in Ni-Cr-Zr brazing filler metal is not easy to diffuse, the substrate is not significantly corroded, and the toughness of the welded joint is higher. The use of Ni-Cr-Zr brazing filler metal can achieve the repair of cracks in ChS88 nickel-based alloy blades. Ojo et al. [19] studied the effects of gap size and process parameters on the microstructure and properties of diffusion brazed joints of Inconel718 nickel-based alloy. As the gap size increases, the appearance of hard and brittle phases such as Ni3Al-based intermetallic compounds and Ni-rich and Cr-rich borides is the main reason for the decrease in joint strength and toughness.

Transient liquid phase diffusion welding is solidified under isothermal conditions and belongs to crystallization under equilibrium conditions, which is conducive to the homogenization of composition and structure [20]. Pouranvari [21] studied the transient liquid phase diffusion welding of Inconel718 nickel-based high-temperature alloy and found that the Cr content in the filler and the decomposition range of the matrix are the key factors affecting the strength of the isothermal solidification zone. Lin et al. [22] studied the influence of transient liquid phase diffusion welding process parameters on the microstructure and properties of GH99 nickel-based high-temperature alloy joints. The results showed that with the increase of the connection temperature or the extension of the time, the number of Ni-rich and Cr-rich borides in the precipitation zone decreased, and the grain size of the precipitation zone was smaller. The room temperature and high temperature tensile shear strength increased with the extension of the holding time. At present, transient liquid phase diffusion welding has been successfully used to repair small cracks in low stress areas and rebuild the tip damage of uncrowned blades [23–24]. Although transient liquid phase diffusion welding has been successfully applied to a variety of materials, it is limited to the repair of small cracks (about 250μm).

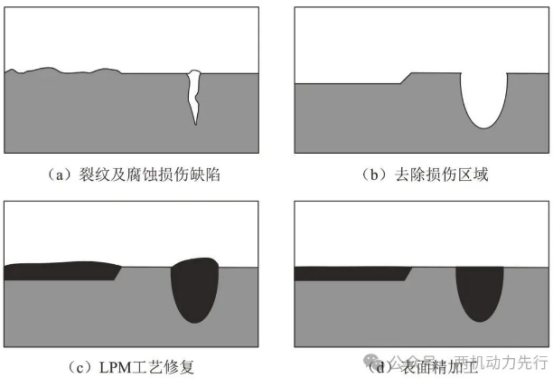

When the crack width is greater than 0.5 mm and the capillary action is insufficient to fill the crack, the blade repair can be achieved by using activated diffusion welding [24]. Su et al. [25] used the activated diffusion brazing method to repair the In738 nickel-based high-temperature alloy blade using DF4B brazing material, and obtained a high-strength, oxidation-resistant brazed joint. The γ′ phase precipitated in the joint has a strengthening effect, and the tensile strength reaches 85% of the parent material. The joint breaks at the position of Cr-rich boride. Hawk et al. [26] also used activated diffusion welding to repair the wide crack of René 108 nickel-based high-temperature alloy blade. Powder metallurgy remanufacturing, as a newly developed method for the original reconstruction of advanced material surfaces, has been widely used in the repair of high-temperature alloy blades. It can restore and reconstruct the three-dimensional near-isotropic strength of large gap defects (more than 5 mm) such as cracks, ablation, wear and holes in blades [27]. Liburdi, a Canadian company, developed the LPM (Liburdi powder metallurgy) method to repair nickel-based alloy blades with high Al and Ti contents that have poor welding performance. The process is shown in Figure 4 [28]. In recent years, the vertical lamination powder metallurgy method based on this method can perform one-time brazing repair of defects as wide as 25 mm [29].

When small-area scratches and corrosion damages occur on the surface of nickel-based high-temperature alloy blades, the damaged area can usually be removed and grooved by machining, and then filled and repaired using an appropriate welding method. Current research mainly focuses on laser melting deposition and argon arc welding repair.

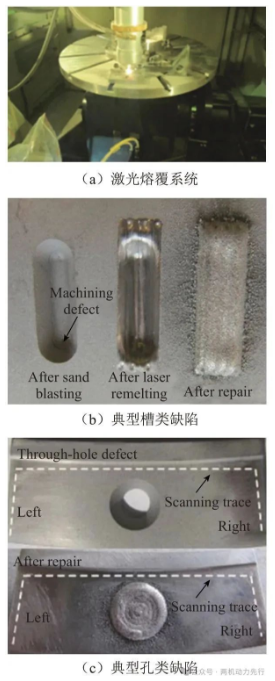

Kim et al. [30] from the University of Delaware in the United States performed laser cladding and manual welding repair on Rene80 nickel-based alloy blades with high Al and Ti contents, and compared the workpieces that had undergone post-weld heat treatment with those that had undergone post-weld heat treatment and hot isostatic pressing (HIP), and found that HIP can effectively reduce small-sized pore defects. Liu et al. [31] from Huazhong University of Science and Technology used laser cladding technology to repair groove and hole defects in 718 nickel-based alloy turbine components, and explored the effects of laser power density, laser scanning speed, and cladding form on the repair process, as shown in Figure 5.

In terms of argon arc welding repair, Qu Sheng et al. [32] of China Aviation Development Shenyang Liming Aero Engine (Group) Co., Ltd. used tungsten argon arc welding method to repair the wear and crack problems at the tip of DZ125 high-temperature alloy turbine blades. . The results show that after repairing with traditional cobalt-based welding materials, the heat-affected zone is prone to thermal cracks and the hardness of the weld is reduced. However, using the newly developed MGS-1 nickel-based welding materials, combined with appropriate welding and heat treatment processes, can effectively avoid Cracks occur in the heat-affected zone, and the tensile strength at 1000°C reaches 90% of the base material. Song Wenqing et al. [33] conducted a study on the repair welding process of casting defects of K4104 high-temperature alloy turbine guide blades. The results showed that using HGH3113 and HGH3533 welding wires as filler metals has excellent weld formation, good plasticity and strong crack resistance, while using When the K4104 welding wire with increased Zr content is welded, the fluidity of the liquid metal is poor, the weld surface is not formed well, and cracks and non-fusion defects occur. It can be seen that in the blade repair process, the selection of filling materials plays a vital role.

Current research on the repair of nickel-based turbine blades has shown that nickel-based high-temperature alloys contain solid solution strengthening elements such as Cr, Mo, Al, and trace elements such as P, S, and B, which make them more crack-sensitive during the repair process. After welding, they are prone to structural segregation and the formation of brittle Laves phase defects. Therefore, subsequent research on the repair of nickel-based high-temperature alloys requires the regulation of the structure and mechanical properties of such defects.

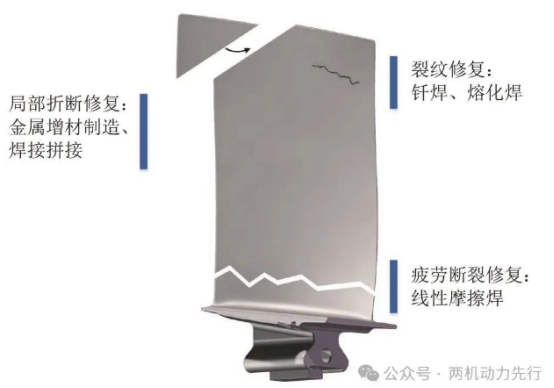

During operation, titanium alloy fan/compressor blades are mainly subjected to centrifugal force, aerodynamic force, and vibration load. During use, surface damage defects (cracks, blade tip wear, etc.), local breakage defects of titanium alloy blades, and large-area damage (fatigue fracture, large-area damage and corrosion, etc.) often occur, requiring the overall replacement of blades. Different defect types and common repair methods are shown in Figure 6. The following will introduce the research status of the repair of these three types of defects.

During operation, titanium alloy blades often have defects such as surface cracks, small area scratches and blade wear. The repair of such defects is similar to that of nickel-based turbine blades. Machining is used to remove the defective area and laser melting deposition or argon arc welding is used for filling and repair.

In the field of laser melting deposition, Zhao Zhuang et al. [34] of Northwestern Polytechnical University conducted a laser repair study on small-sized surface defects (surface diameter 2 mm, hemispherical defects with a depth of 0.5 mm) of TC17 titanium alloy forgings. The results showed that β columnar crystals in the laser deposition zone grew epitaxially from the interface and the grain boundaries were blurred. The original needle-shaped α laths and secondary α phases in the heat-affected zone grew and coarsened. Compared with the forged samples, the laser-repaired samples had the characteristics of high strength and low plasticity. The tensile strength increased from 1077.7 MPa to 1146.6 MPa, and the elongation decreased from 17.4% to 11.7%. Pan Bo et al. [35] used coaxial powder feeding laser cladding technology to repair the circular hole-shaped prefabricated defects of ZTC4 titanium alloy for many times. The results showed that the microstructure change process from the parent material to the repaired area was lamellar α phase and intergranular β phase → basketweave structure → martensite → Widmanstatten structure. The hardness of the heat-affected zone increased slightly with the increase of the number of repairs, while the hardness of the parent material and the cladding layer did not change much.

The results show that the repair zone and heat-affected zone before heat treatment are ultra-fine needle-like α phase distributed in the β phase matrix, and the base material zone is a fine basket structure. After heat treatment, the microstructure of each area is lath-like primary α phase + β phase transformation structure, and the length of the primary α phase in the repair area is significantly larger than that in other areas. The high cycle fatigue limit of the repair part is 490MPa, which is higher than the fatigue limit of the base material. The extreme drop is about 7.1%. Manual argon arc welding is also commonly used to repair blade surface cracks and tip wear. Its disadvantage is that the heat input is large, and large-area repairs are prone to large thermal stress and welding deformation [37].

Current research shows that regardless of whether laser melting deposition or argon arc welding is used for repair, the repair area has the characteristics of high strength and low plasticity, and the fatigue performance of the blade is easily reduced after repair. The next step of research should focus on how to control the alloy composition, adjust the welding process parameters, and optimize the process control methods to regulate the microstructure of the repair area, achieve strength and plasticity matching in the repair area, and ensure its excellent fatigue performance.

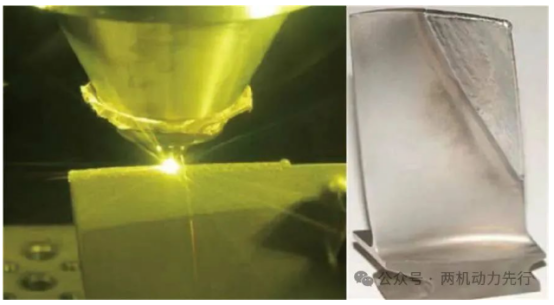

There is no essential difference between the repair of titanium alloy rotor blade damage defects and the additive manufacturing technology of titanium alloy three-dimensional solid parts in terms of process. The repair can be regarded as a process of secondary deposition additive manufacturing on the fracture section and local surface with the damaged parts as the matrix, as shown in Figure 7. According to the different heat sources, it is mainly divided into laser additive repair and arc additive repair. It is worth noting that in recent years, the German 871 Collaborative Research Center has made arc additive repair technology a research focus for the repair of titanium alloy integral blades[38], and has improved the repair performance by adding nucleating agents and other means[39].

In the field of laser additive repair, Gong Xinyong et al. [40] used TC11 alloy powder to study the laser melting deposition repair process of TC11 titanium alloy. After repair, the deposition area of the thin-walled sample and the interface remelting area had typical Widmanstatten structure characteristics, and the matrix heat affected zone structure transitioned from Widmanstatten structure to dual-state structure. The tensile strength of the deposition area was about 1200 MPa, which was higher than that of the interface transition zone and the matrix, while the plasticity was slightly lower than that of the matrix. The tensile specimens were all broken inside the matrix. Finally, the actual impeller was repaired by the point-by-point melting deposition method, passed the super-speed test assessment, and realized the installation application. Bian Hongyou et al. [41] used TA15 powder to study the laser additive repair of TC17 titanium alloy, and explored the effects of different annealing heat treatment temperatures (610℃, 630℃ and 650℃) on its microstructure and properties. The results showed that the tensile strength of the deposited TA15/TC17 alloy repaired by laser deposition can reach 1029MPa, but the plasticity is relatively low, only 4.3%, reaching 90.2% and 61.4% of TC17 forgings, respectively. After heat treatment at different temperatures, the tensile strength and plasticity are significantly improved. When the annealing temperature is 650℃, the highest tensile strength is 1102MPa, reaching 98.4% of TC17 forgings, and the elongation after fracture is 13.5%, which is significantly improved compared with the deposited state.

In the field of arc additive repair, Liu et al. [42] conducted a repair study on a simulated specimen of a missing TC4 titanium alloy blade. A mixed grain morphology of equiaxed crystals and columnar crystals was obtained in the deposited layer, with a maximum tensile strength of 991 MPa and an elongation of 10%. Zhuo et al. [43] used TC11 welding wire to conduct an arc additive repair study on TC17 titanium alloy, and analyzed the microstructural evolution of the deposited layer and the heat-affected zone. The tensile strength was 1015.9 MPa under unheated conditions, and the elongation was 14.8%, with good comprehensive performance. Chen et al. [44] studied the effects of different annealing temperatures on the microstructure and mechanical properties of TC11/TC17 titanium alloy repair specimens. The results showed that a higher annealing temperature was beneficial to improving the elongation of the repaired specimens.

Research on the use of metal additive manufacturing technology to repair local damage defects in titanium alloy blades is just in its infancy. The repaired blades not only need to pay attention to the mechanical properties of the deposited layer, but also the evaluation of the mechanical properties at the interface of the repaired blades is equally crucial.

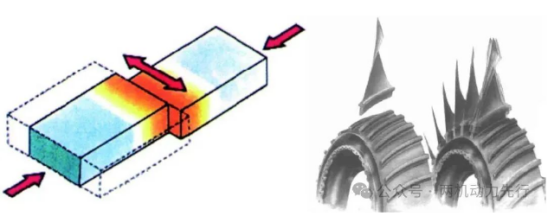

In order to simplify the compressor rotor structure and reduce weight, modern aircraft engine blades often adopt an integral blade disc structure, which is a one-piece structure that makes the working blades and blade discs into an integral structure, eliminating the tenon and the mortise. While achieving the purpose of weight reduction, it can also avoid the wear and aerodynamic loss of the tenon and the mortise in the conventional structure. The repair of the surface damage and local damage defects of the compressor integral blade disc is similar to the above-mentioned separate blade repair method. For the repair of the broken or missing pieces of the integral blade disc, linear friction welding is widely used due to its unique processing method and advantages. Its process is shown in Figure 8 [45].

Mateo et al. [46] used linear friction welding to simulate the repair of Ti-6246 titanium alloy. The results showed that the same damage repaired up to three times had a narrower heat-affected zone and a finer weld grain structure. The tensile strength decreased from 1048 MPa to 1013 MPa with the increase in the number of repairs. However, both the tensile and fatigue specimens were broken in the base material area away from the weld area.

Ma et al. [47] studied the effects of different heat treatment temperatures (530°C + 4h air cooling, 610°C + 4h air cooling, 670°C + 4h air cooling) on the microstructure and mechanical properties of TC17 titanium alloy linear friction welded joints. The results show that with As the heat treatment temperature increases, the recrystallization degree of α phase and β phase increases significantly. The fracture behavior of the tensile and impact specimens changed from brittle fracture to ductile fracture. After heat treatment at 670°C, the tensile specimen fractured in the base material. The tensile strength was 1262MPa, but the elongation was only 81.1% of the base material.

At present, domestic and foreign research shows that linear friction welding repair technology has the function of self-cleaning oxides, which can effectively remove oxides on the bonding surface without metallurgical defects caused by melting. At the same time, it can realize the connection of heterogeneous materials to obtain dual-alloy/dual-performance integral blade disks, and can complete the rapid repair of blade body fractures or missing pieces of integral blade disks made of different materials [38]. However, there are still many problems to be solved in the use of linear friction welding technology to repair integral blade disks, such as large residual stress in the joints and difficulty in controlling the quality of heterogeneous material connections. At the same time, the linear friction welding process for new materials needs further exploration.

Thank you for your interest in our company! As a professional gas turbine parts manufacturing company, we will continue to be committed to technological innovation and service improvement, to provide more high-quality solutions for customers around the world.If you have any questions, suggestions or cooperation intentions, we are more than happy to help you. Please contact us in the following ways:

WhatsAPP:+86 135 4409 5201

E-mail:[email protected]

Hot News

Hot News2024-12-31

2024-12-04

2024-12-03

2024-12-05

2024-11-27

2024-11-26

Our professional sales team are waiting for your consultation.